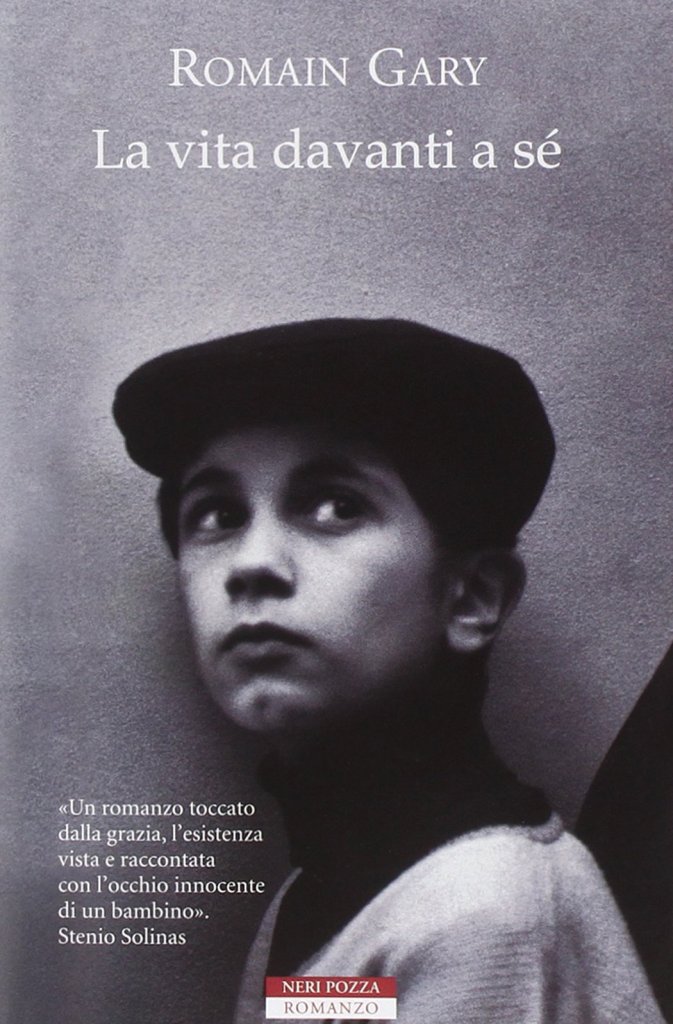

Romain Gary: La vita davanti a sé

“La vita davanti a sé” (Neri Pozza, 2005), prima di essere un film è un romanzo, un grande romanzo di Romain Gary, invitante e tenerissimo nonostante la durezza della situazione e della narrazione che prende i toni foschi e cupi dell’ambiente narrato, le Belleville di Parigi degli anni ’70.

Non ho visto ancora il film tratto da questo romanzo, forse lo vedrò, ma tra un po’, perché per ora voglio lasciare che le parole di Romain Gary continuino il loro lavoro di incisione nel mio pensiero e coltivino e nutrano il piacere e il gusto per una lettura che ho trovato davvero di intensità rara.

La narrazione segue un percorso ciclico, finisce dove è cominciata e, a dire il vero, leggendo l’ultimo capitolo ho avuto bisogno di ricominciare dal primo non perché non me lo ricordassi, ma perché era talmente percepibile la tensione e l’attrazione tra l’ultima parola e la prima che mi era impossibile non lasciarmi trascinare dal ciclo ininterrotto della vita narrata con le parole e lo sguardo di Momo, piccola creatura (10 anni che poi si riveleranno 14 per ragioni di amore) musulmano figlio di una prostituta che lo ha affidato alle cure di Madame Rosa (ebrea sopravvissuta ai campi di sterminio, ex prostituta che con l’avanzare dell’età smette il “mestiere” e apre una sorta di asilo di accoglienza per i figli delle prostitute fino al loro affidamento presso famiglie che li accolgano).

La storia di Momo sorprende perché include la storia del mondo di quegli anni, ma vista dalla parte dei derelitti, gli abbandonati, i giudicati, gli esclusi che, però, rivelano una capacità di aggregazione e mutuo soccorso di molto superiore a quella che ci si aspetterebbe dai ricchi e raffinati che appartengono a una categoria superiore.

Oltre la storia, intensissima, di cui non rivelerò nulla perché i lettori ne scoprano la bellezza e la sensibilità, nel romanzo di Romain Gary c’è tutto il mondo, ci sono temi politici e morali, c’è uno sguardo al dolore fisico e all’eutanasia, c’è attenzione e cura per le diversità culturali e religiose, c’è lo sguardo critico verso chi rifiuta i derelitti e c’è il coraggio di uomini e donne o omosessuali che nella semplicità del proprio amore genuino scoprono il vero potere della vita.

C’è una donna, Madame Rosa, provata dall’esperienza personale (sia quella nel Velodromo d’Inverno e dell’internamento nei campi di sterminio, sia quella come prostituta) che non prevaricherà mai la vita di Momo, che è capace di essere madre pur non essendolo, di garantire insegnamenti ed equilibrio pur non avendoli sperimentati nella propria storia personale, abile a insegnare amore e valori che non siano spendibili attraverso il proprio corpo, ma grazie ai legami umani che, unici, sono necessari per rafforzare la spina dorsale di un ragazzo come Momo, solo e abbandonato se non fosse per quella donna vecchia e brutta, grassa e irascibile che ha saputo insegnargli ad amare e che lo proteggerà fino alla fine. Una storia, mi sembra, nella quale appaiono tratti tipici dell’autore al punto che nei due protagonsiti sono riconoscibili le sue peculiarità: da una parte l’autore somiglia a Madame Rosa per la sua attenzione al corpo che si debilita che introduce al tema dell’eutanasia, dall’altra a Momo per il coraggio di un’anima che cresce e scopre amore oltre i confini dei pregiudizi e delle discriminazioni.

Ancora moltissimo c’è da dire su questo romanzo, moltissimi gli spunti che stimolano la ricerca e il pensiero, la condivisione e l’accoglienza; molto si può dire sulla sensibilità attenta e vivace con cui vengono narrate situazioni, condizioni e persone, quella sensibilità che è madre del dialogo e del confronto, ma anche madre di tutte le madri che imparano e insegnano ad amare oltre la relazione biologica con i figli e che si assumono la responsabilità della vita dell’altro.

“La vita davanti a sé” (Neri Pozza, 2005) di Romain Gary è un romanzo da amare parola per parola, lasciando che ciascuna penetri e vinca il silenzio indifferente del non amore.

“La vita davanti a sé” (Neri Pozza, 2005), before being a film is a novel, a great novel by Romain Gary, inviting and very tender despite the harshness of the situation and the narrative that takes on the dark and gloomy tones of narrated environment, the Belleville of Paris of the 70s.

I have not watched the film based on this novel yet, maybe I will do, but in a while, because for now I want to let Romain Gary’s words continue their engraving work in my thinking and cultivate and nourish pleasure and taste for a reading that I found really rare in intensity.

The narrative follows a cyclical path, ends where it began and, to tell the truth, reading the last chapter I needed to start over from the first not because I didn’t remember it, but because the tension and attraction between the last word and the first was so strong that it was impossible for me not to let myself be carried away by the uninterrupted cycle of life narrated with the words and gaze of Momo, a small creature (10 years that will later turn out to be 14 for reasons of love) Muslim son of a prostitute who entrusted to the care of Madame Rosa (a Jewish survivor of the extermination camps, a former prostitute who with the advancing age stops her “job” and opens a sort of asylum for the children of prostitutes until they are entrusted to families who welcome them).

The story of Momo is surprising because it includes the history of the world of those years, but seen from the side of the derelict, the abandoned, the judged, the excluded who, however, reveal a capacity for aggregation and mutual aid far superior to the one which we would expect from the rich and refined who belong to a higher category.

Beyond the story, very intense, of which I will not reveal anything so that readers can discover its beauty and sensitivity, in Romain Gary’s novel there is the whole world, there are political and moral themes, there is a look at physical pain and to euthanasia, there is attention and care for cultural and religious diversity, there is a critical gaze towards those who reject the derelict and there is the courage of men and women or homosexuals who discover the true power of life.

There is a woman, Madame Rosa, tested by personal experience (both the one in the Winter Velodrome and internment in the extermination camps, and the one as a prostitute) who will never overrule the life of Momo, who is capable of being mother while not being, to guarantee teachings and balance while not having experienced them in her own personal history, able to teach love and values that are not expendable through her body, but thanks to the human bonds that, unique, are necessary to strengthen the spine of a boy like Momo, alone and abandoned were it not for that old and ugly, fat and irascible woman who taught him to love and who will protect him until the end. A story, it seems to me, in which typical traits of the author appear to the point that in the two protagonists his peculiarities are recognizable: on the one hand the author resembles Madame Rosa for his attention to the weakening body that introduces the theme of euthanasia, on the other hand to Momo for the courage of a soul that grows and discovers love beyond the boundaries of prejudice and discrimination.

There is still a lot to say about this novel, many ideas that stimulate research and thought, sharing and welcoming; much can be said about the attentive and lively sensitivity with which situations, conditions and people are narrated, that sensitivity that is the mother of dialogue and comparison, but also the mother of all mothers who learn and teach to love beyond the biological relationship with their children and who take responsibility for the life of the other.

“La vita davanti a sé” (Neri Pozza, 2005) by Romain Gary is a novel to be loved word for word, letting each penetrate and overcome the indifferent silence of non-love.

Ottime recensioni e tutti ottimi libri..

"Mi piace""Mi piace"

Grazie, mi fa piacere che gradisca, la lettura è condivisione, come la scrittura.

"Mi piace""Mi piace"

😊

"Mi piace""Mi piace"